Cognition

When Teaching Mirrors Learning Series

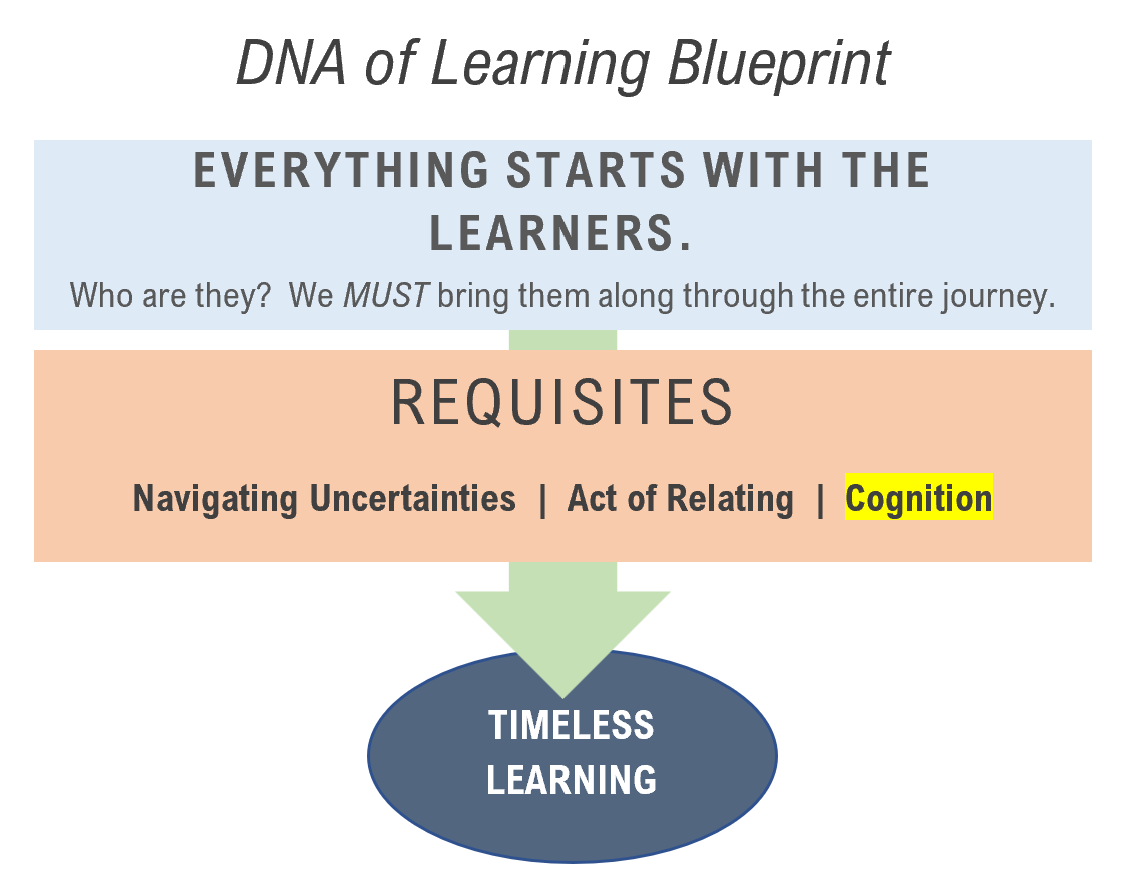

Unpacking The DNA of Learning Blueprint

©2023

Each article in this 15 part series systematically unpacks the DNA of Learning Blueprint for kindling the spirit of learning and re-starting our passion as educators. The collective series will represent a comprehensive outline of fundamental requirements for timeless learning across ages and disciplines.

Part 5: Requisite 3 Cognition

“How will I teach this?” is not the same as “How will my students learn this?”

Why the Blueprint for Learning?

The combined elements of biologic DNA and experience form unique individuals for sure, however, the way the brain acquires and accumulates is far more similar than diverse among humans. Understanding the brain’s learning functions, how it acquires new knowledge and builds on past understandings, is imperative to teaching and learning. Devoid of this, our so-called “best practices” parallel the hit or miss of a baseball player in the batter’s box.

No Rocket Science without the Learning Sciences

We have learned so much from cognitive sciences about the brain and learning. The pandemic disruptions have led to thoughts about what our future world of schooling might entail. The tensions in teaching today underscore how complicated and situational teaching is. It’s not rocket science—it’s far more complex and difficult than rocket science. No packaged program or list of best practices can capture the extraordinary subtleties involved in making on the spot decisions continually each day, after day, after day.

Deep understanding of human cognition as it relates to what we call “learning” can foster subtle differences in instruction leading to magnified, long-term shifts in outcomes. Students deserve to work with educators who are versed in memory formation, recall and transfer. And educators will find joy in their thriving students… a win-win for all.

Preservice Programs: Where are our universities?

Daniel Willingham, Professor of Psychology at UVA, has contributed with the need to employ practices aligned with the findings on the science of cognition. Dr. Willingham’s writings along with his work with “Deans for Impact,” an initiative of the Schools of Education across ten universities (Deans for Impact, 2016), demonstrates a distinction between prospective educators who have understandings of learning sciences as contrasted with those who do not. The interpretations and decisions made by those with a background in learning sciences clearly places their students at an advantage for learning. This work makes clear the imperative for teaching approaches consistent with what we know about how learning takes place. A few of the learning science components address such queries as:

- What is needed to support initial acquisition of knowledge?

- Are there instructional implications for acquiring, retaining and accessing memory and recall?

- Are there ways to manage cognitive load on working memory?

- What is the role of interleaving in learning?

- Does right-left hemisphere matter in teaching?

- Is it true that we only use a fraction of our brain?

Understanding Cognition

We taught it—they demonstrated it today… yet tomorrow there’s little residue. Why don’t they remember? The term “learning” is generally referenced in ways that are not, in fact, learning. Forgetting typically means that we didn’t process sufficiently to generate memory in the first place. What does the mind have to do to make memory? What causes short vs long-term memory? Can recall be enhanced? Are there ways to apply and transfer memory? Knowledge leading to answers for the above questions must be essential learning for all educators. It’s time to unpack the fundamentals of cognition that lead to learning. Getting a degree in cerebral functioning is not necessary to learn pivotal understandings everyone must know and apply. Fundamental knowledge about the brain and learning are requisite for those leading the learning journey.

Cognition: Beyond regurgitation

Reciting something in the moment suggests that short-term memory has placed the information where it can be accessed while the current context is still available. The difficulty comes when the patterns of practice surrounding today’s activities cease… and we go to another class… go home overnight… and the initial connections to information are no longer available. Synaptic strength weakens and memory fades. The next day we are apt to see blank looks from children about yesterday’s work. Frustrating and all too familiar, if not predominant. Many so-called ‘great’ students get A’s because they excel in capacity for short-term, semantic recall. They gather and organize information, memorize quickly and readily

|

|

reconstitute it. This is rewarded handsomely in the traditional culture of schooling. But what of those whose strengths differ? Stephen Tonti illuminates this suggesting that the acronym ADHD is less about “attention deficit” and more about “attention difference” (Tonti, 2019). What about truly understanding how to apply knowledge, understand the analogies of meaning and readily transfer concepts across topics to new areas of thought?

DNA of Learning Neuro-Moves

As examples of practices that are supported by learning sciences, we have briefly unpacked five imperatives that must be in all educator’s toolboxes. These are expanded in Part s 7-11.

Context is essential for capturing the arena in which new information resides. This provides cues to meaning, relationship and improves initial processing efforts. “Billy, I know you are interested in engineering, how would these concepts apply to you in your possible career”? “Mary, your interest is different from Billy’s, you mentioned fashion as a goal, but in what way do you see the connection?” “Take 5 minutes and turn to your partner and talk about how learning this concept is important to your work.” Learners can increase active processing/attention through personal reference as they construct understanding and purpose. Context provides relevance to the topic under consideration. When a leaner is introduced to new ideas and concepts, seeing relationships to what is already known or experienced begins to ground associations. Context is the vehicle that expedites both new and deeper understanding.

Pattern/Classification is what the brain does naturally from birth. In the absence of prior, existing understandings, patterns provide a means of generating an initial sense of the unchartered world. Is this similar to something I already know? Different? How? Does it matter? While the brain is acquiring new ideas, skills, content, and understandings it is efficient to cluster like things—using less working memory to hold newer information while continuing to process for understanding. Initial formation of groups provides greater understanding across venues. Then, the learner can begin to re-work current knowledge and transfer it to aligned or even unrelated topics. This capacity demonstrates understanding at a deeper, more applied level. “Saul, you are good at finding patterns with color or geometric shapes. What patterns can you find that apply to the different authors we’ve been reading?”

Dual coding occurs when visual and verbal cues are EXPLICITLY and SIMULTANEOUSLY merged. When we actively use dual modes to process, our brain exercises multiple pathways. When we directly link the visual processing (items tangibly or mentally available) with the verbal processing, we provide greater cues for comprehension, recall and transfer of learnings. As we use external images and props, we need to keep in mind that our goal is to eventually transfer external cues into internally accessed assets. A teacher could adjust many requests of students by suggesting, “There are several ways you might choose to demonstrate your understanding of the emotions we’ve discussed. Pair with someone to generate both a drawing/image and a short story of when you have felt that way.”

Emotional Tags. No meaning, no memory (Levitt, 2010). At all ages ~ perceived importance, value and/or personal connections increase attention and processing for retention. The mental conclusion of “not important” suggests that little meaning (value) is indicated. That which has only minimal impact on learners can, by definition, have no significant emotional base for memory. When harnessed, emotion supports and bolsters the attentional system to persist through moments of struggle. Emotional “tags” are inputs with meaning for the individual. We know all too well that when our students do not find meaning in material, they seldom are motivated to work in earnest to remember after the fact. Emotion does not mean drama. It signifies meaning and purpose. Meaning comes through both positive and negative emotions. “Students, you each identified a job you would like to have when you graduate. What is it about that work that appeals to you? Why? Can you name the dominate emotion you would feel when doing that work?”

Social Functions. Social interaction causes substantial neural activity, growth, and processing. Building capacity in academics, decision making, managing of emotions, empathy for others, establishing and maintaining positive relationships are all potentiated via social aspects of learning. The brain is directly and powerfully shaped by interactions with others through a sense of belonging, acceptance, feeling worthy, and building community. Being accepted by peers provides emotional security and a safer environment for learning. The initial task at the beginning of every year is to establish a community of learners who can and will work together productively. Social wellbeing and emotional safety are essential for optimal learning to occur. Learning activities without adequate synchronous discourse greatly reduces the provocation of thought (thinking), which is paramount to memory making. Interacting provides give and take, examination, options, differences of perspective, argument, agreement, prioritization, and many other opportunities for feedback that solo experiences cannot. “Once you’re all done digging into your area of interest, pair up with someone, share what you’ve found, why you find it interesting and how you might use your knowledge.”

Moving to Tomorrow…

The requisite of high impact cognition cannot be bypassed or minimized. Too much is at stake for YOUR class, YOUR organization, YOUR satisfaction at work… and most importantly THEIR learning. These required components have a huge return on investment. Theirs—and yours!

Citations:

* Greenleaf, Robert. (2005). Brain Based Teaching. Greenleaf-Papanek Publications

* Willingham, Daniel, et. al. (2015). The science of learning. Deans for Impact Coalition. www.deansforimpact.org.