The Act of Relating

When Teaching Mirrors Learning Series

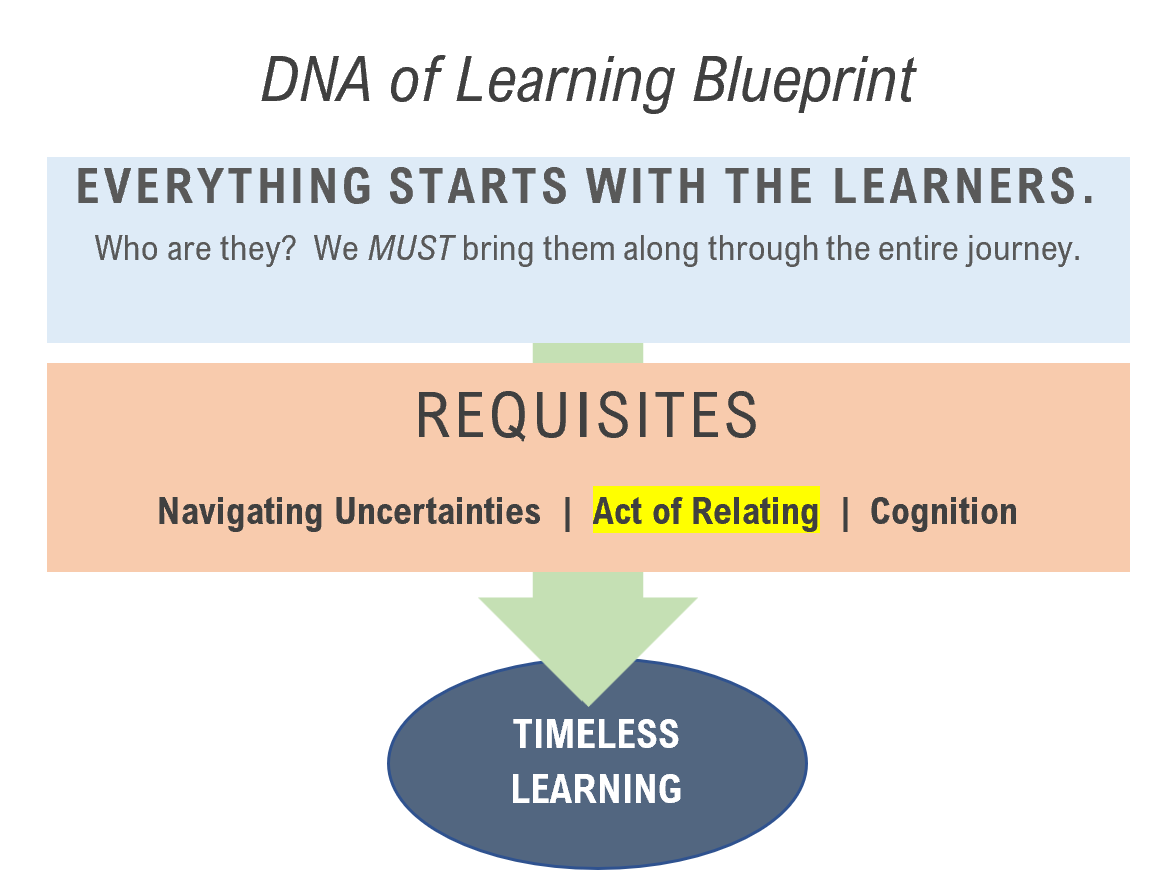

Unpacking The DNA of Learning Blueprint

©2023

Each article in this 15 part series systematically unpacks the DNA of Learning Blueprint for kindling the spirit of learning and re-starting our passion as educators. The collective series will represent a comprehensive outline of fundamental requirements for timeless learning across ages and disciplines.

Part 4: Requisite 2: The Act of Relating

When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows, not the flower.

Out of the COVID ashes…Relating is Key

Let’s start by exploring how learning takes place. Imagine you are in a class, course or workshop— having the experience that the professor or presenter is on autopilot covering the lesson content and not really interested in taking questions or delving far from a seemingly rehearsed script. Ask yourself, what are you feeling at this time? What was your brain telling you about how important the information was? Even if you were intently interested in the beginning… what tends to gradually happen to your enthusiasm as time wears on? It’s been years since most adults have been in a daily, semester long class, so let’s go back there for a moment. Day after day, our students are expected to sit in a room, follow the direction and script of the primary adult in the room, and be totally engrossed and interested in the topic at hand. Pause and imagine… what does that feel like under the best of circumstances?

Now imagine you are not interested in the content… or that the presentations are generic with no relevance; or that you feel like a burden to question, feel like a number, or that you are a relative unknown amidst the others seated about you. How’s it going for you? What would it take to restore the initial interest in learning you might have had at some point? It is the response to this last question that began our journey almost a year ago as we examined, what does it take to become engaged, to be motivated, and to persist in the learning process? We knew better than to move the chairs around on the deck of the Titanic. That ship has sunk over and over with past initiatives. One more reorganization of the deck chairs isn’t going to change the outcome. Before we pour more resources into CIA based efforts (like the deck chairs), we need to focus on why the ship is sinking. It would be foolhardy to plant a garden with expectations of high yield, without first preparing the soil in which it must grow. The qualities within the soil, based on the plant’s needs will surely impact growth and production. As good as the curriculum, instruction and assessment design might be, if it bypasses the most important aspect of assessing readiness, growth will not happen. Without fully understanding the learners in front of us, who they are, what they need, and how these things drive their thirst for learning—they will become distracted with the weeds that have grown up around them and with the lack of nutrients particular to their survival. They will wither away. Attention to the student-prior to curriculum, instruction and assessment expectations-will dramatically improve the production of learning. The bypassing of what comes first, knowing the interests and the needs of the student, we will only perseverate the strong detachment this generation of learners has with this place called school. We have a century of evidence across many schools showing this result.

The Act of Relating to Others, Process, and Ideas

Some students get good grades and test scores no matter what their schooling is. But what of their learning to learn beyond the allure of grades and scores? When they stop playing the game of schooling, what capacities remain? Whether a student is motivated by grades or not, our relationship with them will be the most important aspect of our time with them—and more importantly, for their learning disposition both within and beyond the classroom experience. Will our influence be to support today’s assigned studies or more permanently, to impact their world beyond this day?

|

|

So, just how important are relationships to learning? Think of a favorite educator and/or a memorable subject you engaged in. Unpack, beyond surface reasons, why this person came to mind. Underneath everything, such as interest in a subject, doing well in a subject, the teacher’s sense of humor, the teacher’s expertise… lies a relationship that s/he developed with you and your personal interests. S/he understood something beyond the content of the subject matter and shared their passion for a greater understanding. Relationships, between people, their interests, and important learnings are the essential glue that promotes active engagement, perseverance to understanding and a work ethic that processes beyond grades, to sustained memory. What we remember most, in fact, is the importance a person played in our willingness to put forth effort, support our efforts in constructing capacities and celebrating our accomplishments. It is largely impossible to maximize growth without a purposeful, productive relationship.

The Art of Relating to Others

Several years ago, I hired a veteran Reading/Writing Specialist for a Grade 3 teaching position. She was highly recommended and a good fit for the school. She had never had her own classroom but was eager to take it on. As the second week of school began, I visited her classroom to see how all was going. Much to my surprise, the classroom was quiet, except for the new teacher’s voice. There were no smiling faces, no questions, no comments… no energy. During a follow up meeting, the teacher admitted she couldn’t get her students to “open up.” They behaved OK and did their work, but none seemed to be at ease or having a good time. What was missing were the relationships that support interactions. Though attention to curriculum was there, little thought was given to building community. After some discussion she decided to start each day with a morning meeting, where she and each student could share something of interest about themselves. The simple, short conversations quickly led to relationship building, fostering a sense of community. Learning became personal, more engaging, and fun. Relationships first, teaching and learning follow.

The Art of Relating Ideas and Process

Soon, the teacher mentioned above began to explore other aspects of how things “relate.” She discovered that knowing her students well was essential, but just the beginning. Next, she looked at the curriculum and units she had planned to identify major concepts and big ideas. Did students “relate” to this? She asked herself as she planned daily lessons, “What questions could be used that would help students better relate the content and big ideas to their world?” She developed the following filter questions to ask as she prepared every lesson:

“What context does this learning reside in that my kids can relate to?”

“How can I draw their past knowledge and experience into the big ideas of the lessons?

“When a student acts out, is it attention seeking or connection seeking behavior?”

“How can I help them understand each other, empathize, and relate sufficiently to treat each other respectfully?

“What process/options would give them choice and relevance in how they go about this work?

As a result of this shift in planning, she found students more eager to participate in class/groups. Discussions were more comprehensive with much more personalized input. Beneath every behavior is a feeling and a fundamental need. When she designed lessons that met student needs, the students became the drivers of their learning, moving forward, while the teacher played the role of the coach.

Moving to Tomorrow

Step 1: Plan each unit/lesson with opportunities for students to relate with one another. Accepting and respecting differences in our schools has become a major challenge. Teachers have a tremendous opportunity to provide classroom practices and strategies that foster relationships to highlight our similarities and collective strengths. Facilitating discussions around what connects us together, student interests and important issues in their lives-rather than our differences-makes for cooperative community interaction. What is relevant that they will relate to? Which options will help them process to understanding and transfer?

Step 2: As relationships with others evolve, relating to concepts and ideas must also develop for deep learning to occur. This shift in the planning process provides opportunities for students to discuss their personal interests with each other and, by identifying primary take-aways from the lesson, discuss how transferable their learning is to their own future. When learners can relate through context, experience, or prior knowledge, they become more interested, motivated and apt to persevere.

Step 3 Relating also applies to the learning process. Throughout the leaning process, students are reinforced with background knowledge through discussions with peers (Part 12: Neuro-Move Social Interaction). Many times, anchor charts are used as prompts to help students understand processes for new learning. As a result, the brain more readily develops a schema that relates parts within a concept or big idea (see Neuro-Move Context). This enables familiarity(see Neuro-Move Emotional Tags). for more purposeful processing. Similarly, when we can connect parts of new learning to prior knowledge and experience, we free up the cognitive load (Larson, 2019) on working memory and can actively process similarities and differences that shape our understanding.

The requisite of relating cannot be bypassed or minimized. Without a connection to each other and our work, we’re back in the batter’s box taking random swings at errant pitches. Too much is at stake for YOUR class, YOUR organization, YOUR satisfaction at work… and most importantly THEIR learning. These required components have a huge return on investment. Theirs—and yours!

Citations:

* Greenleaf, Robert. (2005). Creating mindsets: Movies of the Mind. Greenleaf-Papanek Publications

* Larson, Sarah 2019. Cognitive Load Theory: how has it changed my teaching? World Press

* Deans for Impact (2016). The Science of Learning, https://deansforimpact.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/The_Science_of_Learning.pdf.